Notes from the field

Rethinking Assessment in the Age of AI

May 13, 2025

5 min read

A Familiar Panic, With Good Reason

It’s not just media hype—educators are deeply, sincerely anxious about what AI means for student writing and learning. A recent report from Tyton Partners found that more than 60% of educators believe AI tools will make it harder to assess what students truly understand. Meanwhile, usage of tools like ChatGPT has quietly exploded in classrooms, often without clear policies in place.

As someone who teaches and regularly evaluates written applications, I’m immersed in these conversations. They’re urgent, emotional, and full of conflicting instincts. I understand the fear—but I also see a bigger opportunity. AI isn’t the end of writing. It’s a wake-up call to reexamine what we’re really assessing when we assign written work. Are we evaluating thought? Process? Communication? Or are we simply defaulting to tradition?

The Problem with What We’re Really Grading

I spent years TAing for a theater analysis class where students had to dig into a play, take a position, and defend it with evidence. Giving feedback on the thinking behind a student’s position—the originality of their interpretation, the coherence of their logic—was the most meaningful and transformative part of teaching.

But in practice, when time was tight, I often found myself spending more time correcting sentence structure, adjusting word choice, or suggesting transitions than on the depth of the ideas. It’s easier to fix the form than to wrestle with substance. I’ve seen the same thing happen in offices: when people are stretched thin, feedback defaults to slide formatting or font size—not content.

We’ve come to expect writing to carry too much pedagogical weight. We use it to assess everything from grammar and clarity to critical thinking and effort. That’s an impossible burden for one medium to carry. It creates superficial feedback loops—and students know it.

We’re All Being Confronted Right Now—And That’s a Good Thing

This moment of reckoning isn’t limited to schools. AI is prompting similar identity crises across nearly every knowledge-based profession. When a tool can instantly draft a memo or strategy doc, what is my role as a worker? What value do I add?

I think back to my graduate program in 2020, when COVID-19 hit. Our professors—some of whom had been teaching from the same PowerPoint decks for years—were suddenly asked to reinvent everything. They learned Zoom overnight. They reshaped curricula. They opened the curtain to show us the mess and modeled how to lead through uncertainty.

That’s the kind of pedagogical courage this moment calls for. AI is a disruption, yes—but it’s also an invitation. An opportunity to adapt in public, with humility and curiosity. And to bring students into that process as collaborators, not just passive recipients.

The Havruta Model: Ancient Practice, New Technology

Havruta is a centuries-old Jewish practice of paired study—students sitting in dialogue, not to recite facts, but to question, challenge, and interpret together. It’s one of the oldest and most enduring models of collaborative learning. The power lies in the exchange, the friction, the shared meaning-making.

And remarkably, that’s also what AI is beginning to make possible. Tools like ChatGPT and Claude offer dialogic interfaces. But most students use them transactionally: “Write me an essay on X.” That’s not havruta—it’s outsourcing.

To unlock the true potential, we need to shift the frame. From command → output to question → exploration. From transactional to sculptural. From mechanical to mutual. When a student iterates, refines, and challenges an AI’s suggestions, it begins to look like learning. And that’s the pedagogical potential I see in this new medium.

Reimagining Assessment: Process Over Product

What if we assessed the thinking process—not just the final result? Imagine students submitting a polished paper and their AI chat transcript. We’d see their missteps, their breakthroughs, their questions, their edits. We’d see them think.

Admittedly, this is likely to change the role of the teacher in the classroom, or at least with writing - we might see teachers move from editors and grammar instructors to coaches or philosophical interrogators. This change might feel intimidating, but when I think about the teachers I know and the reasons why they feel called to teach, these moments of coaching and mind-development are cited over their love of subject every time.

This piece you’re reading is itself a kind of experiment in that. I’ve refined my thinking in conversation with AI. The drafting, redrafting, reflecting—it's all part of the process. And for once, that process of thinking is documentable.

This approach also allows us to disentangle key skills:

- Oral communication: best assessed through presentations, peer interviews, and live discussions.

- Critical thinking: surfaced in how ideas evolve over time, how questions are posed, how perspectives shift.

- Writing fluency: still valuable, especially in synthesis and clarity—but no longer the catch-all proxy.

It’s no secret that over recent years employers have sounded the alarm that new grads often lack "soft skills"—oral communication, adaptability, collaboration. Perhaps it’s because we’ve never created distinct opportunities to practice and assess them on their own terms.

This Crisis Runs Deeper Than AI

Data from the National Center for Education Statistics shows U.S. reading proficiency declining over the last decade. And a 2021 Gallup poll found nearly half of American adults didn’t read a single book that year.

The fear that students won’t learn to think or write critically didn’t begin with AI. AI is just a spotlight. The real issues—declining literacy, overstretched teachers, underfunded schools—have been with us for a long time. If we want to build deep thinkers and strong communicators, we need a broader ecosystem of interventions: reading clubs, debate teams, oral storytelling, reflective writing.

AI might accelerate the crisis—but it didn’t cause it.

Not All Writing Is the Same

At work, I write often—and mostly to be understood. Clear, informative, direct. For that kind of writing, AI is a helpful tool.

But I recently joined a creative writing group. We meet in person, write by hand, and share reflections. That time feels sacred and it builds on my pwn private practice of journaling and writing poetry. For this kind of writing—writing as a form of self-knowledge—I don’t want AI in the room. I write for the process and the thoughts I work out between handprinted letters.

There’s a fear that students will stop caring about writing if they use AI. But I think that underestimates human creativity. Calligraphy didn’t die when word processors arrived and the appeal of fancy ink pens and orderly notebooks ripe for capturing flowing thoughts are still strong.

If the goal were to really build a culture and affinity of writing and reading, we'd build a curriculum around deep textual engagement, rigorous debate, and creative writing as a process tool; but most classrooms don't look like that today and instead are filled with standardized tests, reading passages over full texts, and 5-paragraph essays that read like a rubric.

This could be the opportunity to do thinks differently.

A Closing Invitation

So let’s not meet AI with panic or prohibition. Let’s meet it with thoughtful experimentation. This is a chance to revise—not just what we teach, but how we recognize and nurture growth in a new landscape.

Consider this an invitation to slow down and ask: What is writing for? What kinds of thinking do we want to encourage? How can we design learning experiences that make space for exploration, dialogue, and surprise?

This isn’t a call to abandon rigor or abandon writing—it’s a call to reorient around the purpose of education itself. Not as gatekeeping, but as guidance. Not as surveillance, but as stewardship.

Because the future isn’t about controlling learning. It’s about witnessing it, cultivating it, and co-creating it.

More articles

Newsroom

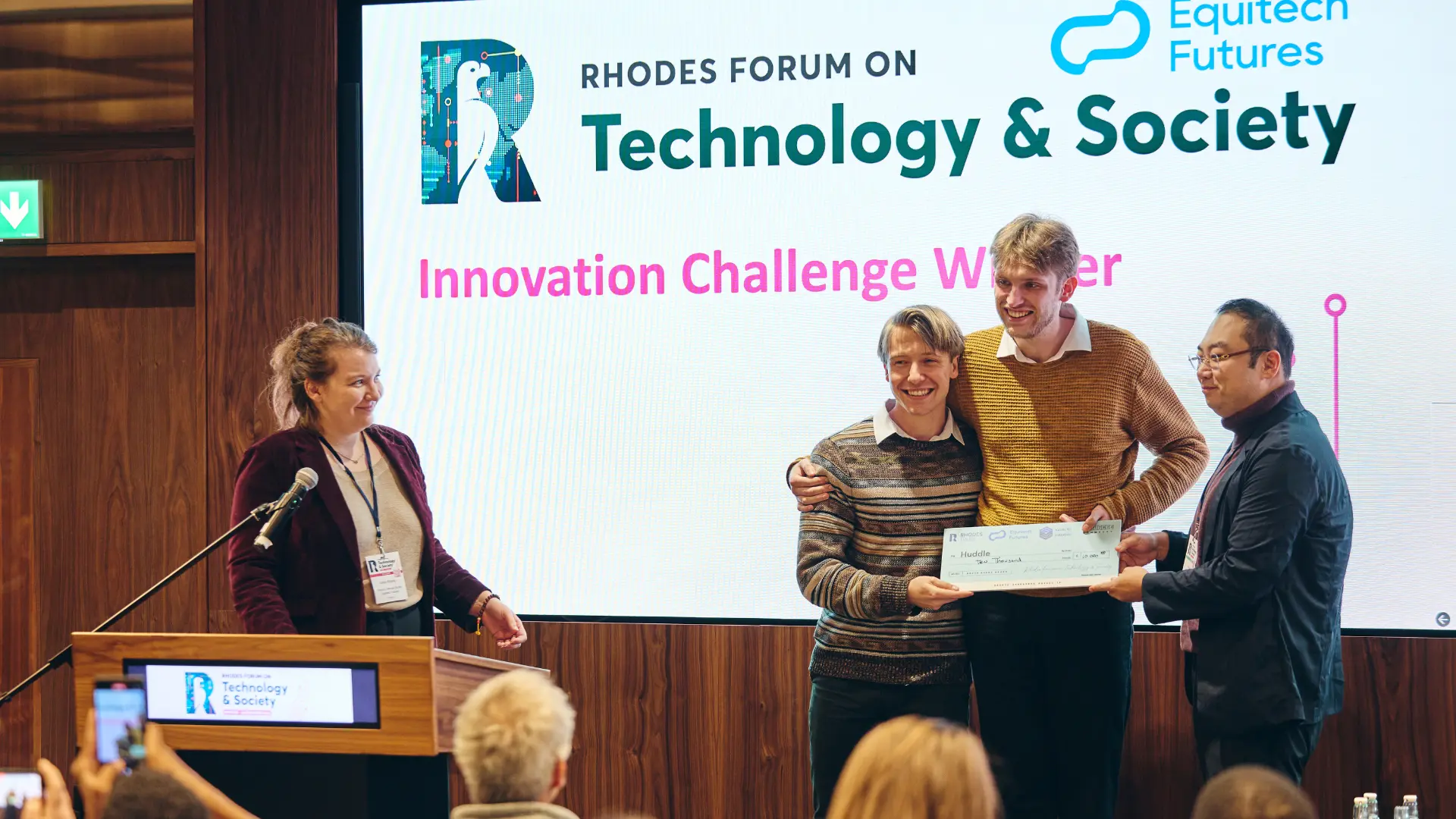

Otieno Collins Junior Reflects on His Journey from Capstone Project to Prize-winning Startup

.webp)

Newsroom

No Innovator Left Behind: How Equitech Futures uses philanthropic capital to maximize impact

Newsroom

.webp)

.webp)

.webp)

.webp)

.webp)

.webp)

.webp)

.webp)

.webp)