Newsroom

The AI Skeptic Who Refused to Sit Out

Oct 29, 2025

5 min read

Swathi Srinivasan doesn't use ChatGPT. She hasn't touched it since 2022, when she first learned about the technology's environmental cost. As a PhD candidate at Harvard Chan School of Public Health and former caseworker with Boston Healthcare for the Homeless, she can recite the statistics that keep her up at night: 80% of Google's data output involves potable water for cooling data centers. Billions of gallons. Greenhouse gas emissions concentrated in exactly the low-income communities she's dedicated her career to serving.

And yet, she's building a company with AI.

The contradiction isn't lost on Swathi. "My dream situation was to do this project with as little AI as possible," she admits. But that dream collided with a harder reality: when technological revolutions happen, vulnerable communities get left behind. And Swathi refuses to let that happen again.

The Problem That Wouldn't Let Go

The idea for Civic Helper didn't start in a boardroom or accelerator. It started with birth certificates.

During her time as a social services caseworker, Swathi spent her days navigating a bureaucratic maze that would be comic if it weren't so cruel. Her clinic kept stacks of birth certificate forms—paper forms that had to be filled out by hand, mailed to different offices depending on the state, tracked manually, and then re-entered into computer systems. For people experiencing homelessness, these documents aren't just paperwork. They're the gateway to everything: food stamps, housing applications, reduced-fare transit cards, Social Security benefits.

"It shouldn't be complicated to have access to your birth certificate," Swathi says, her frustration still fresh. "It shouldn't be complicated to apply for food stamps if you don't have food. You should have food. It is that simple."

But simple problems don't always get simple solutions—especially when the people who need them most are the ones society has decided to ignore. Swathi saw people go without food because they'd lost their EBT card and couldn't navigate the phone system to get a replacement. She watched caseworkers drowning in paperwork while their caseloads climbed higher. She counted the hours lost to forms that could have been spent with people who desperately needed support.

"We don't need extremely complicated tools," she reflects. "Some of the major issues are very simple and relate to very simple things. We can fundamentally change access to food and money for food by making one form easily navigable."

The Walk That Changed Everything

It was only after leaving that job—in the brief window before starting her PhD—that Swathi had the bandwidth to see the solutions that had eluded her on the front lines. During a walk with her friend Michael Litt in New York, she was trying to recruit him to public service.

"What would I do?" Michael asked.

"Actually," Swathi said, "I could think of a lot of processes that tech could be really useful for."

The admission felt strange coming from her mouth. Swathi is very quick to “villainize technology”, as she puts it. But she's also intellectually honest enough to recognize its strengths: processing large amounts of information quickly, making repetitive tasks easier, cutting through bureaucratic red tape.

Michael, a software engineer who'd met Swathi years earlier at a high school science fair, saw the opportunity immediately. They'd been having conversations about technology and society for years—Swathi pushing toward public service, Michael being pragmatic about what tools could actually accomplish. This was their chance to put both philosophies into practice.

"If governments had resources that were more readily available and digitized, we wouldn't need to exist," Swathi says. "The goal is that the people who operate these systems make things available." But they don't. And while they don't, people go hungry.

Pragmatism in the Face of Pandora's Box

Swathi describes herself as an "AI skeptic," but she might be better termed an AI pragmatist. Not because she's softened her environmental concerns—she hasn't—but because she's clear-eyed about the choice in front of her.

"I have no option but to be pragmatic now because it exists," she says. "Without my choice in the matter and without these big discussions on the climate."

This is the part that keeps her up at night: AI's infrastructure isn't just environmentally costly, it's inequitable. Data centers drive up electricity costs that are distributed across entire communities, with low-income people spending the highest percentage of their income on power. The people using AI the least pay the most for its existence.

"I will always caveat my work with the fact that I am a skeptic and that I do not believe it should require the resources that it requires in a world where we have limited resources," Swathi emphasizes. "But if it is going to exist—which it does—we do need to be pragmatic. And I don't just mean to justify the work that is happening. I mean that the people using this need to care about the resources they are pulling from."

This is where her partnership with Michael becomes crucial. While Swathi pushes on the environmental and equity implications, Michael ensures they're using the technology responsibly—playing to its actual strengths rather than getting swept up in hype.

"When people talk about AI now, they're talking about LLMs like ChatGPT-style chatbots," Michael explains. "They have their strengths and weaknesses. The major strength is being able to quickly find the needle in the haystack." For Civic Helper, that means helping caseworkers quickly locate the right application form for a birth certificate in any state—something that would otherwise require navigating fifty different bureaucratic systems.

"One of the weaknesses is when you ask these chatbots to give you an answer to a theoretical problem that isn't in the training data, it will hallucinate," Michael continues. "We're being very particular about how we deploy the technology to make sure we're playing to the strengths of AI and not playing into the hype cycle."

The Relief on Their Faces

A few days before the interview, Swathi showed the prototype to former caseworker colleagues to get their feedback on early product design and functionality. The reaction was immediate and visceral.

"They just looked at it and they were shocked," Swathi recalls. The design is almost comically simple: drag in a PDF form, fill out the fields that appear, click download. No data uploaded to the internet. No complicated interface. Just a straightforward tool that does exactly what it promises.

"The relief," Swathi says, still processing it. "It felt like a small thing, but it's actually a big thing."

The prototype currently handles Massachusetts birth certificates, but the vision is to expand across all fifty states and eventually to other vital documents—Social Security applications, housing forms, reduced-fare transit cards. Every document that stands between someone and survival.

The Stakes Are Too High to Opt Out

Swathi is adamant about one thing: she refuses to let vulnerable communities be left behind by technological advancement. Again.

"We saw this with the Industrial Revolution, moving from farming to industry," she points out. "We saw it with early internet access during COVID. Internet's such a cool thing, but so many people don't have it, and that makes access to information so difficult. The people that got left behind were kids who are low-income, communities of color—exactly the communities I'm hoping to support."

This is the heart of why an AI skeptic is building an AI company. Not because she's changed her mind about the environmental costs. Not because she thinks the technology is being deployed responsibly at scale. But because Pandora's box is already open, and the question now is: who gets included in the conversation?

"When these technological changes happen, who are we including and who are we excluding?" Swathi asks. "Who are we bringing with us and who are we letting fall through these graphs of inequality? The three richest people in this country all use AI in some capacity, and it's going to disproportionately impact people with the lowest income and their job access. We're expecting that a quarter of jobs won't exist in ten years. That is dramatic, and we have no game plan for that. That's irresponsible."

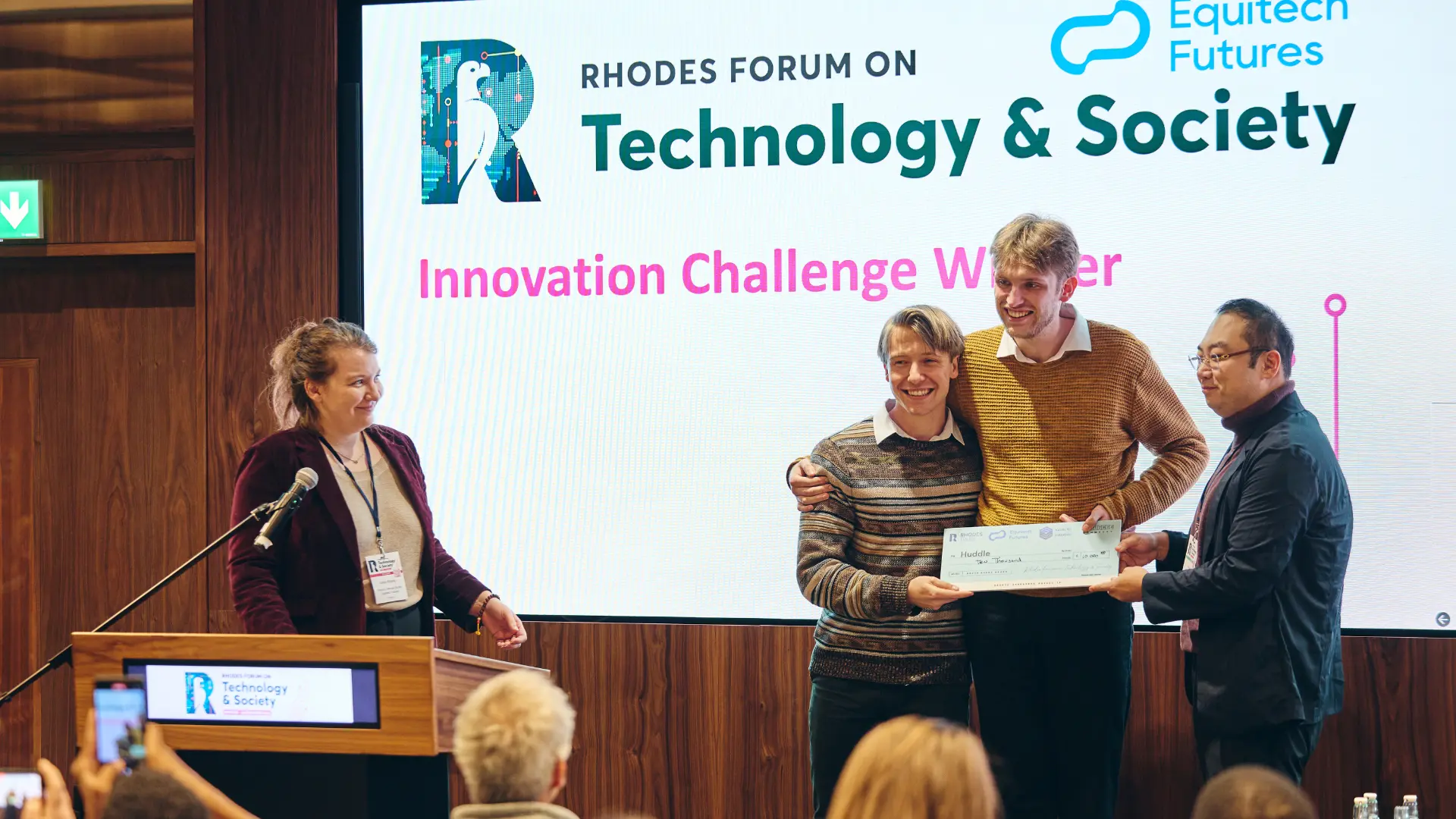

Her solution isn't to stop technological advancement—she knows she can't. It's to ensure that the people most impacted by these changes have a seat at the table. By building Civic Helper, by participating in forums like the Kevin Xu Innovation Challenge with Equitech Futures and the Rhodes Trust , by having conversations with people who might not otherwise think about environmental costs or equity implications, she's inserting these concerns directly into spaces where decisions get made.

"By having folks involved in the conversation, we can fundamentally improve the standards of not just the technology as it's applied, but as it's created," she argues.

Building Better, Together

The story of Civic Helper reveals something essential: we need more skeptics building, not fewer.

"I obviously wouldn't be working on this project if Swathi didn't have the experience to realize this was a problem that needed to be solved," Michael acknowledges. "The fact that I'm able to work with someone who has firsthand, hands-on experience—feedback is invaluable. If it was just software engineers building this from some written specification, it would be the blind leading the blind."

Their partnership proves that these diverse viewpoints don't just coexist—they make each other sharper. Swathi's skepticism keeps Michael honest about environmental costs and real-world impact. Michael's technical expertise gives Swathi's frontline experience a path to scale. Together, they're building something neither could create alone.

Looking ahead, they plan to expand Civic Helper across all fifty states for birth certificates, then gradually add other document types. They're building a network of point people—people working in housing advocacy, substance use disorder response, overdose prevention—to test the tool and provide feedback.

"The goal is that if governments end up using these services, I'm happy to support that," Swathi says. "When you don't have the bandwidth, these resources can be not just useful but life-saving. I mean, I have seen people go without food because they don't have their food stamps. If we can simplify just one thing in that person's day, it can be life-saving."

It would be easy for Swathi to opt out entirely. To focus on her PhD, to advocate from the sidelines, to let someone else wrestle with the moral compromises. But the caseworkers she worked alongside don't have that luxury, and neither do the people they serve.

The future of technology won't be built by optimists alone. It needs skeptics too—the ones who count the costs, question the assumptions, and still show up to build something better. It needs people like Swathi Srinivasan: uncomfortable with contradictions, clear about consequences, and utterly unwilling to let one more person go hungry because a form was too hard to fill out.

CivicHelper is a finalist in the Kevin Xu Innovation Challenge 2025. The challenge supports innovators building AI tools that empower people to lead more productive and meaningful lives.

More articles

.webp)

Newsroom

No Innovator Left Behind: How Equitech Futures uses philanthropic capital to maximize impact

Newsroom

.webp)

.webp)

.webp)

.webp)

.webp)

.webp)

.webp)

.webp)

.webp)