Newsroom

The Billion-Dollar Information Gap: How OpenDoor Catches People Before They Fall

Oct 27, 2025

5 min read

Maria was a preschool teacher until her landlord raised the rent. One day she had a place to live. The next day, she was evicted.

She spent her nights calling helplines, waiting on hold, being redirected endlessly. Housing organization. Food bank. Job training program. Each one operating in isolation. Each one unable to see what the others were doing. Maria bouncing between them all, falling further through the cracks with every transfer.

The resources existed. The funding was there. Maria just couldn't access any of it.

"That's the moment that framed OpenDoor for me," says Diya Sreedhar, who met Maria at an LA shelter where Diya had volunteered for four years. "Homelessness is not really about poverty as much as it's about information and equity."

The Infrastructure No One Built

When officials from the Department of Health and Human Services sat down with Diya and her co-founder for user interviews, they shared a startling figure: "This is pretty much a billion dollar industry."

Not the size of the problem. The size of the waste.

Billions of dollars flowing into services that people can't access. Caseworkers overwhelmed. Housing programs with empty slots because eligible people don't know they exist. Food assistance going unused. Job training programs searching for participants while unemployed people search for opportunities.

"If you can help caseworkers, law firms, government officials, government benefit providers reach the people they're trying to help, a lot of money stops going to waste," Diya explains.

The leaders at shelters and free clinics where Diya volunteered knew this intimately. They'd been wanting a centralized tool for over a decade. But the fragmentation persisted. And here's what happens when systems can't talk to each other: people who arrive hopeful get ground down by red tape until they become chronically homeless—a situation that's basically impossible to escape.

"I saw so many people fall through the cracks because they had a lot of hope for a service they wanted to access and then just never could," Diya reflects. "All the red tape that prevents them from getting help is what ends up making them chronically homeless."

OpenDoor isn't trying to create new services. It's building the infrastructure to connect the ones that already exist—what one user called "a shared nervous system for the care ecosystem."

Prevention at Scale

Here's what makes OpenDoor different from other navigation tools: it's designed to catch people before they fall all the way through.

When most people picture homelessness, they picture Skid Row in LA—chronic homelessness, people who've been without housing for so long that traditional interventions rarely work. But before Skid Row, there's always a transitional period. Someone loses their job. Rent goes up. A medical emergency depletes savings. These are normal people hit with misfortune who haven't yet fallen all the way down.

"When you say someone lost their job, you don't often think of that as being a precedent to now I've lost my house," Diya notes. "Those are areas we really want to target."

The pilot results from LA this summer show what's possible when you catch people during that transitional window. One story illustrates the potential: a diabetic patient missed work due to hospitalization. OpenDoor's system flagged them early and referred them to both rental assistance funding and food delivery—before they reached crisis stage. Before missing one paycheck cascaded into eviction.

Across their initial partnerships with transitional housing organizations in LA, residents were connected to verified help about three times faster than before. Follow-through on referrals increased by 50%. Not because Diya's team created new resources, but because they built the connective tissue the system was missing.

Tech That Augments, Not Replaces

OpenDoor's approach combines two core tools: an AI-powered service matcher and a job training agent. The service matcher gets people personalized information on resources they're eligible for—not a generic list, but options that match their specific circumstances. When someone doesn't qualify for a service, it connects them to a caseworker who can help navigate around barriers.

The job training agent helps people prepare for entry-level job interviews and gain certifications—the kind of one-on-one coaching that caseworkers want to provide but rarely have time for.

"If we can offload some of the less important tasks to technology and make the whole process more efficient, then that extra time can be spent really investing in the people we're advocating for," Diya explains. "The homeless issue is not just a housing problem. They have so many different things they need to control at once, it just becomes unmanageable. If we're letting technology do the grunt work, that's a great way to avoid caseworker burnout as well as information desensitization."

This distinction matters. While other tools focus on single touchpoints—helping with one form, one application, one service—OpenDoor is building something broader: infrastructure that coordinates across housing, healthcare, food assistance, and workforce development. It serves both the people seeking help and the overburdened systems trying to provide it.”

Building 50 Partnerships in Four Months

The speed of OpenDoor's traction reveals how desperate the need was. In their initial LA pilot, Diya and her co-founder built 50 different partnerships: transitional housing organizations, healthcare providers, women's shelters, job training programs. Each one had been operating in isolation. Each one immediately saw the value of connection.

"Everything kind of works in isolation in this system," Diya explains. "There's one organization for housing, another for food, another for job training. People are trying to help, but everything is disconnected."

Now Diya is expanding to Boston and San Francisco, testing whether OpenDoor can adjust to different rules in different states while remaining continuously in demand. The goal is ambitious: a tool that works in a rural Alabama library as well as urban New York. Embedded in shelters, clinics, libraries—anywhere people are trying to rebuild their lives.

She's also expanding the scope beyond transitional homelessness to adjacent inflection points: prison reentry programs, where job retraining could prevent recidivism. People who just lost their jobs, before they lose their housing.

"Before, people kind of feel like they're applying and looking for help full time," Diya says. "Whereas with this tool, they can focus on actually rebuilding the lives that they may have lost."

Why Now, Why Tech

A decade ago, if you cared about homelessness prevention, you'd start a nonprofit. Hire caseworkers. Open an office in one city. Help people one by one, constrained by your organization's capacity.

Diya chose differently, and the choice wasn't arbitrary.

"I've worked on a lot of similar projects in healthcare, using technology to improve patient and clinician workflows," she explains. "Through those experiences, I've seen how modern technology can really integrate many different systems. Whereas before, you might have an NGO that operates in a certain city, in a certain state, and it's difficult to expand past that because you have to take a lot of initiative to keep things running."

With technology, the infrastructure can scale. Local organizations can plug in without rebuilding from scratch. Information can flow across systems without requiring each caseworker to memorize fifty states' worth of eligibility requirements.

"We can actually build technology with communities rather than for communities," Diya emphasizes. "Before, there were never these types of tools that could be so personalized and so all-encompassing."

But the technology isn't the point. The connection is.

Opening Eyes Upstream

One of Diya's most striking insights is about who benefits from OpenDoor beyond the people experiencing homelessness: legislators and public health officials.

"I see the opportunity for people upstream, like legislators and public health officials, to be more grounded in the reality of their constituents through OpenDoor," she says. "The stories we're seeing in our pilots—hopefully OpenDoor kind of opens eyes of the people in power to where exactly the gaps are."

When a diabetic patient gets flagged for rental assistance before reaching crisis, that data point matters. When 50% more people follow through on referrals because they actually understand their options, policymakers should know. When billions of dollars in services go unused not because of lack of need but because of lack of connection, that's not just a service delivery problem—it's a systems design failure.

OpenDoor makes those failures visible. It turns anecdotes into data. It shows legislators exactly where people are falling through, and why.

Infrastructure for Community Care

Four months into building OpenDoor, Diya Sreedhar has proven something that shouldn't be surprising but somehow still is: when you give young people the tools and support to build solutions, they don't just build apps. They build infrastructure. They build systems that connect other systems. They build bridges that governments couldn't—or wouldn't.

Maria shouldn't have spent her nights calling helplines with no solution in sight. The preschool teacher who lost her apartment when rent went up shouldn't have become another statistic in a billion-dollar system that couldn't connect her to the help that already existed.

The resources were always there. The funding was always there. What was missing was the infrastructure to coordinate community care.

Now it exists. And it's scaling.

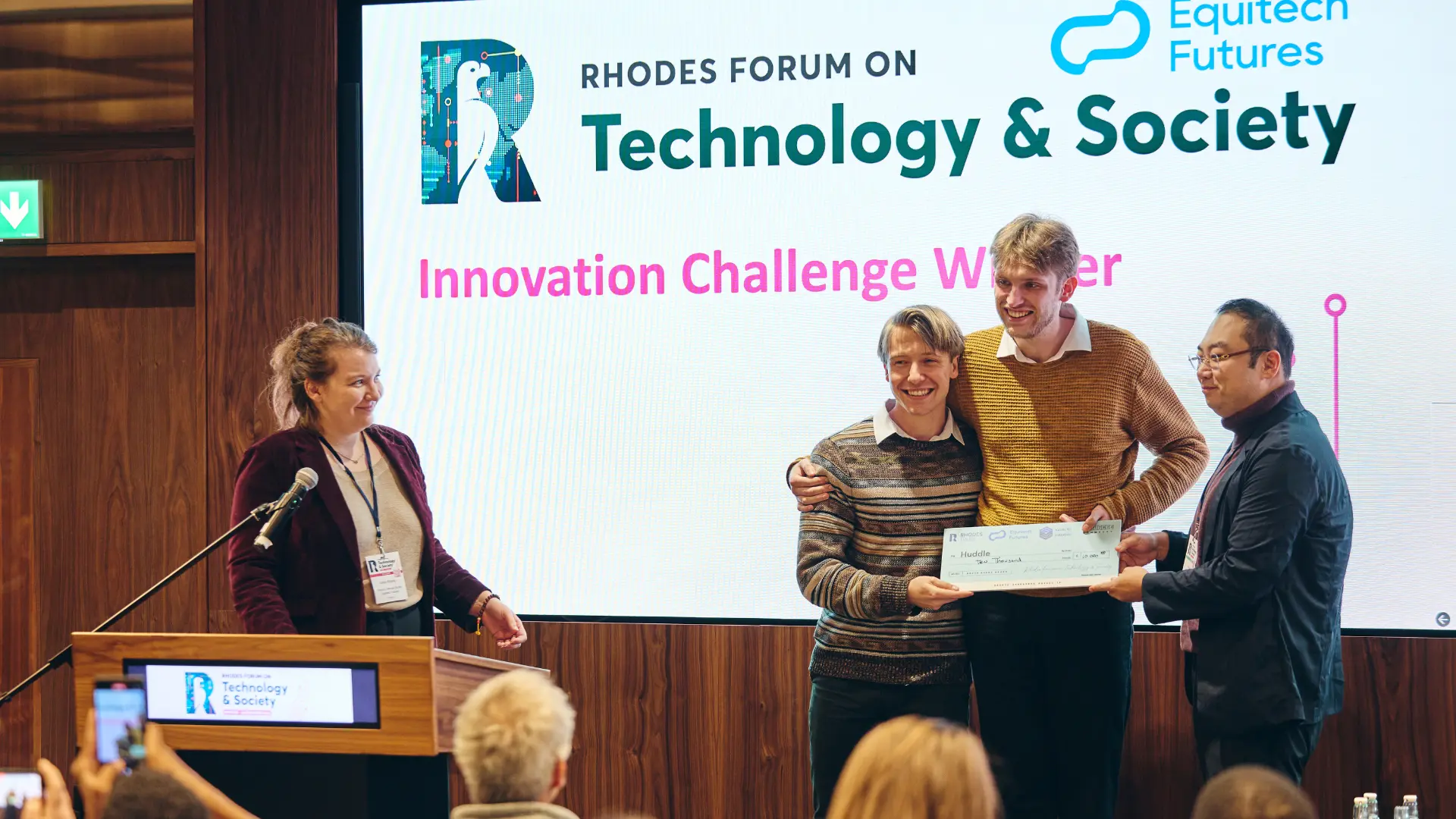

OpenDoor is a finalist in the Kevin Xu Innovation Challenge, part of the Rhodes Forum on Technology & Society. The challenge supports innovators building AI tools that empower people to lead more productive and meaningful lives.

More articles

.webp)

Newsroom

No Innovator Left Behind: How Equitech Futures uses philanthropic capital to maximize impact

Newsroom

.webp)

.webp)

.webp)

.webp)

.webp)

.webp)

.webp)

.webp)

.webp)